“Less Rules, more intuition.”

Alan Cohen

Despite a growing demand for creativity, today’s organizations still lack a widespread problem-solving ability at the individual level. The way to achieve this is to make creative problem solving simple and intuitive.

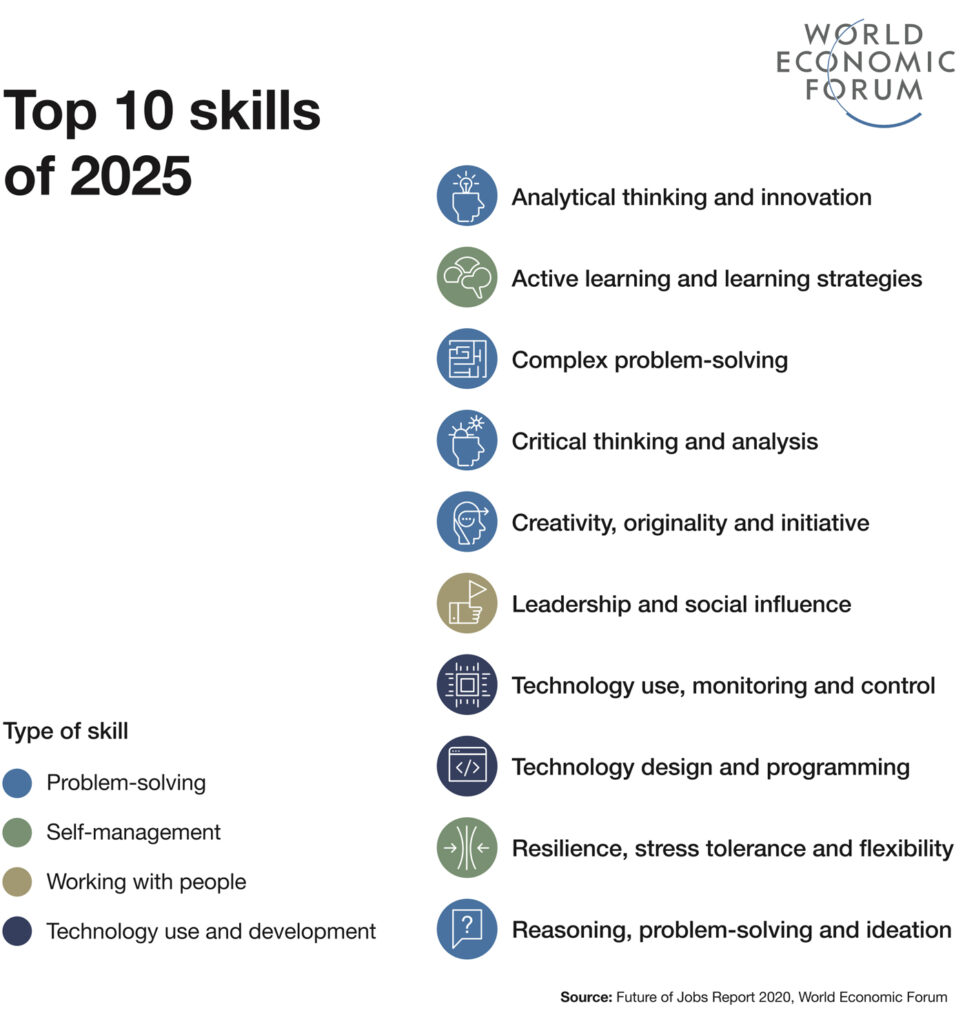

As Gabriella Rosen Kellerman and Martin Seligman point out: “One island of stability in the sea of conversation about the future of work is the conviction that our jobs will become increasingly creative” 1. The World Economic Forum, McKinsey, and nearly every major think tank seem aligned around this hypothesis, offering heaps of data to support it.” Take for example The World Economic Forum’s “Top 10 Skills of 2025” 2. Five of them are about problem solving, as shown in figure 1 (those marked with blue circles).

Figure 1. The World Economic Forum’s Top 10 Skills of 2025. The five skills marked with blue circles are about problem solving.

“The trend is not just about the delegation of rote tasks to automation” – Kellerman and Seligman explain – “it’s also about the accelerating pace of change and the increasing complexity of business, which demand original responses to novel challenges far more frequently than ever before.” 3 Moreover, reorganizing work in order to make it more agile by emphasizing self-initiative, requires that all the workforce be capable of making important decisions that are in line with the organization’s strategy and culture.

Despite a growing demand for creativity, today’s organizations still lack a widespread problem-solving ability at the individual level. After decades and millions spent in creative training, it appears that organizations have been unable to build up this skill. There are excellent group methods like design thinking, but what about people who have to tackle a problem individually? Or for teams that lack a facilitator? Today, the ability to solve problems is totally reliant on individual talent and experience. How can we broaden the creative competences base within organizations?

Making it easier

If we want to enable people to become proficient problem solvers, we must make it easier for them. To do that, we must forget techniques and focus on principles. Techniques are artificial and often complex. Instead, when people understand the “whys” of a discipline, it will become part of their mindset and they will be able to apply it intuitively. Intuition makes the problem-solving process simpler.

For over a century scientists, psychologists and researchers have studied how creativity works and have come to the same conclusions. Their model is divided into of four stages:

Sensing is the first method for learning how to generate intuitions at will in problem solving. Sensing works based on the principle that intuitions emerge in the conscious mind in the form of feelings. You will notice that every time you have an intuition, this will not emerge as the result of reasoned thinking but as feelings. If feelings are the channel through which we come up with intuitions, then when solving a problem, you should ask yourself: “What do I sense about this problem?” and through the channel of feelings you’ll be able to have direct access to the insights of the intuitive mind.

Intuition allows you to obtain information unconsciously that go beyond the scope of the analytical mind. I recall the case of an advisor who had to start working for a consulting firm and wanted to practice Sensing in order to learn more about its owner. Before we started Sensing I asked him what he thought of this person. He replied that he thought this person was very able, had great energy, was essentially positive, but his only flaw was that he was somewhat egotistic.

When I subsequently asked him to practice Sensing, he confirmed those impressions, adding that there was something else he had perceived: the impression [feeling?] that that person’s “own personal interest was in conflict with other people’s”. I advised the consultant not to walk away from the situation, but to continue exploring it, while trying to verify this information. A week later the consultant called me and said: “You won’t believe this. Yesterday I met with a group of professionals who know the owner of the consulting firm, and they spoke very negatively about him. They told me he is untrustworthy and that they all had a bad experience with him.”

Being able to tackle problems starting from the ability to understand their essence, their critical points, provides us with an invaluable advantage in problem solving. However, problem solving does not end with having an intuition: it is an iterative process that gradually explores the problem by following a continuous series of intuitions and tests.

This is how Jonas Salk, the inventor of the polio vaccine, describes the process: “Reason alone without intuition can easily lead the wrong way. Both are necessary. The way I like to put it is that I might have an intuition about something, I send it over to the reason department. Then, after I’ve checked it out in the reason department, I send it back to the intuition department to make sure that it’s still all right.” 5

The “intuition-check” process is iterated until a solution to the problem is reached, as explained by Bergson 6 . The “intuition-analysis” cycle is iterated until a solution to the problem is reached, as explained by the great French philosopher Henri Bergson 7. Bergson saw the role of intuition as important for arriving at new ideas, after which we should abandon intuition and work on building the body of knowledge, using the new intuitively obtained knowledge.

When we begin to ‘feel lost’, he argued that we should get in touch with our intuition again, often undoing what we have done in the deliberative phase, and continue this process in cycles. As eminent philosophy of science scholar Karl Popper 8 said “there is no such thing as a logical method of having ideas, or a logical reconstruction of this process … every discovery contains … ‘a creative intuition’, in Bergson’s sense’.”

We call the iterative process intuition-check, “Zigzag” and it is what we teach in our training courses. As Tiziana Tonini from Roche says: “With Sensing I learned to solve all kinds of problems in a simple way or [quite easily]. When I have a problem to solve I “do Sensing” and this gives me some indication of which direction to take. I act on the basis of these indications (for example, I compare myself to others, I acquire information, etc.). Then, based on the information I have acquired, I act upon it and “do Sensing” again, which shows me a new direction, on the basis of which I act again, and I continue like this until I’ve solved the problem. This way, the final result is a success, because the solution comes from within me and not from others, and because I move progressively on the basis of my intuition, testing the results at each step. Plus, it’s simple [or easy] because I don’t have to force myself to come up with ideas; ideas emerge on their own, and I just have to execute and readjust [or fine tune] the direction of the shot.”

The Zigzag process is the simplest and most natural – as well as the most effective – way of doing problem solving. Structured methods (you can recognize them by fact that they are defined by acronyms) may be fine for creative professionals, but for ordinary managers they are unnecessarily complicated. Once people know how to do Sensing and are aware of the logic behind the Zigzag process, problem solving becomes simple and intuitive. In this case, everybody will easily learn how to do problem solving and creativity will innervate organizations.

1. G. I Rosen Kellerman, M. E. P. Seligman (2023)

2. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/top-10-work-skills-of-tomorrow-how-long-it-takes-to-learn-them/

3. G. Rosen Kellerman and M. E.P. Seligman, “Cultivating the Four Kinds of Creativity: How people and organizations use them all to innovate.” (https://hbr.org/2023/01/cultivating-the-four-kinds-of-creativity).

4. Sadler-Smith, Eugene. Intuition in Business (pp.452-453). OUP Oxford. Kindle edition.

5. Jonas Salk on “Anatomy of reality. Merging of intuition and reason” (https://johnljerz.com/superduper/tlxdownloadsiteMAIN/id789.html).

6. Bergson, 1911: 238–239.

7. Bergson, H. “Creative Evolution” (L’Évolution créatrice, 1907). Henry Holt and Company 1911, p. 238–239.

8. Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery (New York: Basic Books, 1959), 27-34.

Whether you're curious about features or you want a free trial, we're ready to answer any and all questions.

©2024 Marco Bassani. All rights reserved. Intuitive Thinking®, Sensing® and In-depth Brainstorming® are registered trademarks and the property of Marco Bassani. Privacy Policy